The Journey to Defunding Police in San Jose Unified

By Katherine Leung, art teacher

Spend one afternoon in a Hoover Middle School art class and you’ll hear immediately, exactly how much the police impacts low-income youth. In art classes, students sit at large communal tables. Tall ceilings, an industrial warehouse feel, free range of art supplies, project-based learning, and a hands-off constructivist teaching approach mean that students are talking – all the time.

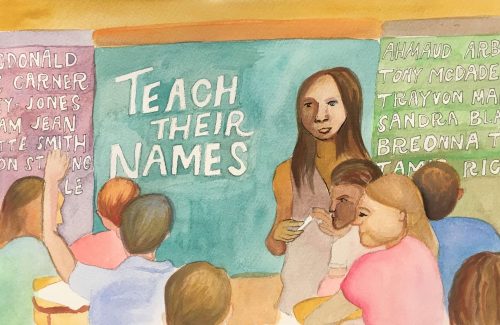

The first year I taught art at Hoover, I assigned homework. Students had to make five free draw sketches and turn it in every Monday. Within a year I scrapped that idea. Homework completion was very low, a typical experience of any teacher that assigns homework in a school with similar demographics. Whenever I asked students why they couldn’t get work done, they shared stories of arrests that happened outside their apartment complex, incarcerated family members that aren’t able to help them, court dates, and ongoing fear of ICE raids. While the media may minimize police violence, the effects of policing on Black and Latinx students and their ability to perform at school is all too real. Student fear and disrespect of police is manifested through acting out – pulling fire alarms and prank calling 911. In art class, their distrust of police is seen in artwork. “Fuck the police” isn’t just a cultural reference, it is a motto to many and a recurring theme in art projects. Street artists, like Keith Haring, is a favorite artist in the curriculum, because of his multiple run-ins with the law while peacefully creating art and stark anti-police symbolism present in his artwork. Anti-police sentiment permeates language, as well. Students use the term “cop” to refer to people they find unfavorable. The two School Resource Officers employed on campus have not fostered any positive relationships with students.

Schools with a larger population of Black and Latinx youth are more likely to have more School Resource Officers (SRO), whereas predominantly white schools in affluent neighborhoods may not house a single officer. There is growing evidence of SRO ineffectiveness in working with students. Seventeen people were shot to death in Parkland, Florida, while an SRO remained outside. Since 2015, video has captured an unarmed Black 16 year old girl being dragged down stairs in a Chicago high school; a Black 11 year old girl being wrestled in a New Mexico middle school; a Black 15 year old girl slammed to the floor in a South Carolina high school; a Black 17 year old boy in a headlock, a Black 14 year old boy punched in the face in a Pennsylvania high school all perpetrated by SROs. A 2018 Advancement Project and the Alliance for Educational Justice report found that there have been more than 60 incidents of police violence in schools from November 2010 to March 2018. A 2018 Washington Post analysis of nearly 200 incidents of gun violence on campus found only two times where a school resource officer successfully intervened in a shooting. It is no longer a case of a “few bad apples” but a highly documented phenomenon seen at various levels, in every state.

SROs actively contribute to the school-to-prison pipeline. The United States has the highest number of incarcerated individuals worldwide. Black and Latinx students are more likely to be subjected to harsher punishments and more likely to be disciplined due to adultification. Districts “around the country have found that youth are being referred to the justice system at increased rates and for minor offenses like disorderly conduct” (Justice Policy Institute). After hearing countless incidents with the police and experiencing police brutality just blocks away from our school, two other BIPOC teachers and I decided to bring the idea of a defunding police resolution to our teachers union.

In the summer of 2020, the San Jose Police Department (SJPD) used tear gas and rubber bullets on protestors. Many people were wounded and a teenage boy hit in the head with a projectile, following a long string of controversy regarding police brutality in various neighborhoods of San Jose. Community activist Derrick Sanderlin was shot with a rubber bullet by police and will suffer lifelong physical health problems. Respected and seen as a mentor to many, Sanderin worked holding implicit bias trainings of new police recruits for many years. We worked with him to write our Derrick Sanderlin Resolution to defund the police, as he worked with two neighboring districts, Alum Rock Union and East Side Union, the two other major school districts in San Jose, in successfully ending their contracts with SJPD.

On June 11th, during the wake of the George Floyd protests, San Jose teachers and school board members worked together to pass a Black Lives Matter resolution in the district. The resolution acknowledged structural and institutional racism, mourned the unnecessary loss of black lives, recognized the experiences of black people, and called for “committing to work for change, with a charge to instill in our youth a belief that every person deserves to live with dignity, be valued for their inherent humanity, and be treated ethically.” With that precedent, we authored the Derrick Sanderlin Resolution with the help of ten other members of the Equity Team of the San Jose Teachers Association, and brought it to local teachers union, San Jose Teachers Association (SJTA) at representative council assembly. Representative Council is SJTA’s police-making body, made up of 110 members, elected to two-year terms by the teachers at each school in the district. The Resolution specifically calls for the rerouting of the $1.38 million typically allocated to SJPD in a SJUSD Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) “toward student support positions and programs such as counselors, school-based social workers, psychologists, restorative justice practitioners, or other mental or behavioral health professionals, as the budget supports, to meet the needs of students. It also advocates for the Superintendent to launch, by no later than August 20th, 2020, an inclusive, community-driven process – involving parents, students, teachers, school administrators, student support staff, San José Teachers Association, and other community partners – for completing a revised District safety plan with strategies for enhancing student learning, safety, and well-being within the District” and to stop the renewal of the contract with SJPD. On July 15th, the Derrick Sanderlin resolution was approved unanimously in SJTA.

Interest in the Derrick Sanderlin resolution reached all corners of San Jose. A corresponding petition on Change.org has received over 1000 signatures in support of police-free schools. A community coalition of parents, teachers, students, and organizers organically formed, called the San Jose Unified Equity Coalition, inviting in anyone open to discussions of student safety. Youth-led organizations such as Silicon Valley Debug and San Jose Strong are in strong attendance. A letter on behalf of organizations in support of defunding the police includes supporters such as Silicon Valley NAACP, ACLU of Northern California, National Center for Youth Law, San Jose Strong, Showing up for Racial Justice Sacred Heart, Together We Will San Jose, Planned Parenthood Mar Monte: Kids in Common, Amigos de Guadalupe Center for Justice and Empowerment, Change SSF, Fresh Lifelines for Youth, and more. Community members demanded the Derrick Sanderlin resolution be discussed at the San Jose Unified school board meetings on July 23rd and August 6th. As a result of union advocacy and endless letters, public comments, and statements from students, parents, teachers, and community organizations, San Jose Unified finally held a Special Session board meeting on August 25th to discuss the role of SJPD. Against the community wishes, there was no formal talk of the Derrick Sanderlin resolution, which had been sent numerous times to each board member by many community members.

With the Special Session agenda set only twenty four hours before the start of the actual meeting, the teachers union president and the three teachers involved in the creation of the Derrick Sanderlin resolution pressed the board about the previously promised presentation time. We finally received five minutes of board meeting time just twelve hours before the meeting. Prior to our verbal-only presentation, over seventy community members spoke for the allotted one hour each in support of ending the MOU with SJPD. Among the commenters passionate about defunding SROs were students who witnessed SROs verbally abusing students of color; students recounting distinct racial profiling in who the SROs at their site choose to engage; a mother who’s black son was targeted, wrongly accused and taken away in handcuffs at school; a public defender whose life’s work involves helping youth that entered the school-to-prison pipeline far too early; supporters that read stories of traumatized youth who wished to remain anonymous; and white activists that acknowledge the privilege of only having to hear such stories. A recurring theme was the undeniable violence at the hands of police nationwide, and for once, we are at a pivotal moment to end the presence in our 41 schools.

We were not met without dissenters. Just the day before the Special Session, a public letter on behalf of twelve principals was went to the board in support of SROs. It stated that “when our students are alleged to have committed a crime, our campus officers are trained to work with school staff and parents as they treat students appropriately as kids” – which begs the question – what crimes do students “commit” that teachers, campus supervisors, counselors, and peer mediators, and administrators cannot already handle? The letter states that “without campus officers, schools must rely on calling 911” – which is what schools are already doing. During the Special Session, the superintendent revealed that SJUSD made exactly 611 calls for police in the last year. The letter ends with “removing officers from our campuses will create a direct and immediate threat to the safety of our students and staff” but ignores the voices of students and staff of color who have already publicly declared time and time again that policers do not make them feel safe. Does it have to be an incident recorded on SJUSD security cameras, specifically, in order to change their mind? Does it have to be an incident involving their own child in order for them to see the problem? Do Black and Brown students not matter?

The key writer of the letter was a white principal notoriously vocal against teachers who are high-risk or caretakers of high-risk choice to work from home during the COVID-19 pandemic school reopening, an individual that clearly enjoys exercising power at the expense of students and teachers of color. Of the only twelve who spoke in favor of keeping police, two were retired police officers themselves. One was a school secretary that stated that police officers helped her this morning get “homeless” people sleeping in a student-less school site just earlier that morning (amidst record evictions and job loss). One was a student who recounted friendships with police officers while at school. One was a non-union teacher that attempted to write his own letter against the SJTA resolution, a thirteen page manifesto that shares his joyous experience at police academy, later revealing his family’s traumatic experience as a result of social unrest in Ireland. His overarching argument is criticizing the resolution’s appeal to popularity and suggests “building stronger, positive relationship” with SJPD despite the forty years opportunity to do exactly that. SJTA members replied with open invitations for discussion and debate, which he ignored. As a non-paying non-union member, this teacher still benefits from union protection such as paid leave, instructional minute and class size caps, and the catastrophic leave bank. Of the signatures in his manifesto, almost half remain anonymous, confronting the good-natured intent of police-supporters, educators that believe colorblindness and power blindness are an accurate lens to view the world. As idealized as a collaborative and productive relationship between police and schools are, the growing accounts of brutality, abuse, and killing on behalf of the police on specifically people of color can no longer be justified.

The Special Session went on for three hours, with a lengthy presentation on behalf of the police, citing just how friendly they really are, the meeting concluded with board members deciding to put out a student survey on their opinion of police. After an endless stream of online surveys regarding school reopening this summer, conducted only in English, it will further disenfranchise the groups that were not present at the Special Session: people scared of being targeted, immigrants, people of color that aren’t familiar with the formal language to navigate board rooms, and most importantly, children. The president of the board stated not to “personalize” this moment as “this is not a black and white issue” multiple times during the duration of the meeting.

While I am honored to be representing my students, elevating their issues that they only feel comfortable mentioning in art class, I am worried that our greatest victory will only be in the teachers union, and not in the school district. A district as large, with colorblind leadership, with numerous instances of corruption and power at the top, may not have the tools to see their own problems, especially if the problems plague a group that is seen as disposable. As a teacher, I will do as much as I can in stopping the school-to-prison pipeline within my classroom. It’s a shame that we came so close, only to be so far away in abolishing police in our district. My heart aches as another video is released of yet another crazed officer brandishing power on a helpless student – as a teacher, for all of humanity.